Urban structure is made up of various different zones.

Within MEDCs there are generally 5 zones: the Central Business District (CBD),

inner city, inner suburbs, outer suburbs and countryside. Each zone tends to

have its own particular land use. The CBD is an area of high density, high rise

buildings which occur because competition for land is high here. CBDs are

normally pedestrianized, contain the main shopping areas, have a bus and train

station, plenty of banks, offices and entertainment venues and cafes. Car

parking is generally found on the edge of the CBD. The CBD is where most

business and commerce is found. A good example for picturing the CBD is the

pedestrianize areas of Leicester City Centre - particularly around the clock

tower.

The inner city is found next to the CBD and mainly consists

of houses in a grid like pattern (think Coronation Street). In the 19th

Century these terraced houses were built to house factory workers who worked in

the inner city factories. They are generally 2 up 2 down houses with an outside

toilet and are found near the canal or railway. When the terraces were built,

there would have also been a factory nearby, as well as a public bath and park

in the area. Each street would have also had a pub or corner shop. During the

1960s many of the factories started to close down, which led to unemployment

and other socioeconomic problems, which in turn meant periods of unrest in many

inner city areas. Many of the old terraces were knocked down and replaced with

flats and maisonettes. In recent years

many of these areas have undergone a period of regeneration, some have had

retail parks built on the former industrial estates, for example Watford Arches

Retail Park. Run down terraces are often bought by investors who adapt the

houses for modern living, adding an inside bathroom and in some cases adapting

houses for the student market. A great local example is Clarendon Park in

Leicester - a very popular area for students of the University of Leicester to live

in. Many of these terraced houses have been adapted to house 2, 3, 4 or 5 students.

Other investors will improve the terraces to appeal to young professionals who

need to access the CBD. This process of renovating the inner city areas is

called gentrification.

The next zone is the inner suburbs. This area contains

housing which is nearly all detached or semi-detached. Mostly built in the

1920s and 1930s, the housing is medium sized, generally has a garden and a few

have a garage. Places of worship, schools and parks are often present as well

as shopping centres which can sometimes be found here.

The outer suburbs are made up of detached houses. These tend

to be large new houses with garages, gardens and trees. In the late 20th

Century housing estates were built in the suburbs, arranging the detached

houses along roads arranged in cul-de-sacs and wide avenues. New shopping

centres, council estates, modern factories and open parks and spaces are found

within the outer suburbs.

The final zone is the countryside. There are few houses

found here, mostly fields, trees and according what I wrote in my GCSE work

book, sheep.

Geographers have created models of what a typical city

should look like. One of the most famous is the Burgess model, also known as

the concentric zone model. As you can see from my drawing above, the order in

which I went through the zones fits with the Burgess model. The idea is that

land values are highest in the centre of the town or city, because competition

his high in the central parts of the settlement. This leads to layout as

mentioned above, with the highest density of buildings in the centre and

density decreasing the further out one goes.

The Burgess model…

Clearly, this will not fit every city, as not every city is

a ‘typical city’. On top of this, the Burgess model was developed before mass

car ownership, which does affect the model as I will look into below. Finally,

the model does not take into account the many people who choose to live and

work outside the city.

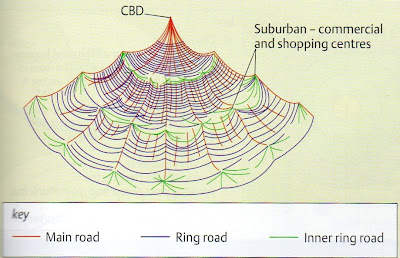

The Hoyt model (see below) aims to solve a few of the issues

with the Burgess model. It is still based on the concentric rings, but also

takes into account the transport and physical factors which affect a

settlements layout, as well as the knowledge that houses were built along main

roads to ensure easy access to the CBD. The model also takes into account that

factories were built along railways and canals, so that raw materials and the

finished products could be transported easily. Some of the other outward developments

acknowledge the fact that many cities grew outwards on the flattest land, as it

was easier and cheaper to build on.

The topic in teaching…

From looking in my work book, when I learnt about this, it

was a case of copying down diagrams from the board and working through things

as a class. I’m not really sure how far I could deviate from this, but one

activity I did see that I thought was really good is shown below…

This was given to us as a sheet of 9 jigsaw pieces which we

had to cut out and fit together to make the town. Following from this we then

coloured in the sections to show how the town grew - from just the centre in

the 1700s, to the growth of the 1900s and then the extension to add the

suburban estates in the 1950s. The key on the bottom left hand side of the

picture notes the corresponding colours to years of development.

References

http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/gcsebitesize/geography/urban_environments/urban_models_medcs_rev1.shtml

http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/gcsebitesize/geography/urban_environments/urban_models_medcs_rev2.shtml

http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/gcsebitesize/geography/urban_environments/urban_models_medcs_rev3.shtml

http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/gcsebitesize/geography/urban_environments/urban_models_medcs_rev4.shtml

http://www.s-cool.co.uk/gcse/geography/settlements/revise-it/urban-morphology

.jpg)